Earlier this year I was asked to write an article for The Linnean Society’s membership magazine, after spending time in their fascinating archives researching one of our main characters Ethel Sargant. Out of all the characters in our show, Ethel is the one that has changed the most since we started writing The Cambridge First All-Ladies Fire Brigade. Each time we discover something new about this brilliant botanist, it changes what we understand about her personality, and shifts how we want to portray her on stage.

Here’s a version of that article. Although it doesn’t have all of the Linnean’s beautiful illustrations included, it does have a few little bits of research that I couldn’t fit into the official printed version.

Don’t get a petunia up your petticoat, it’s time to meet Ethel Sargant!

Portrait of Ethel Sargant by F Ernest Jackson school held at Amgueddfa Cymru (Museum Wales) and Ethel’s own microscope, held at the Lawrence Room, Girton College’s Museum. Ethel was pleased that the portrait included her microscope, but complained that her “sense of humour was left out” (she still bought thirteen extra copies for nine guineas)

Who was Ethel Sargant?

When we began researching Ethel, the most obvious place to start was the Linnean Society archives, the membership organisation where her reputation as a skilled botanist was allowed to flourish. For starters, we found her entry in the Fellow’s database and a two-page obituary published in the Society’s 1918 Proceedings.

Described as ‘gifted and distinguished’, Ethel was born in 1863 as the third daughter of barrister Henry Sargant. The Sargants were a comfortably rich, well-connected London family that counted judges, headmasters and artists amongst Ethel’s siblings. This sits in stark contrast to our other four main characters: Hertha was working as a governess to support her widowed mother before she joined Girton, Charlotte and Annie were vicar’s daughters from Lincoln and County Tyrone in Ireland, and orphaned Ida was sent to Girton when her Guardian didn’t know what else to do with her. Compared to the rest of the Fire Brigade, Ethel’s level of privilege was the exception, not the rule.

After being educated at the progressive North London Collegiate School London, Ethel went on to study Natural Sciences at Girton. She did not particularly excel in the notoriously challenging Tripos Examinations, emerging with a Second Class in Part I and Third Class in Part II.

Ethel worked briefly at the Jodrell Laboratory at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew but for the most part family ties kept her at home in Reigate, caring for her mother and sister for much of her working life. This was no barrier to her botanical research, however, as she created what would be the affectionately monikered ‘Jodrell Junior’ lab in her mother’s garden. Here she studied the anatomy of seedlings and the ancestry of angiosperms before putting forward her influential ‘A Theory of the Origin of Monocotyledons’ in 1903.

In the Linnean Society’s collection of letters, we also found that the naturalist Marcus Hartog – who happened to be Hertha’s cousin – wrote to the Linnean’s council in 1900 to suggest that women should be accepted as fellows:

“The Society rather refuses help in not opening its gates to such workers as Eleanor Ormerod and Ethel Sargant… such quiet good workers…”

In 1904 Ethel did indeed became one of the first women elected as Fellows of the Linnean Society, then in 1906 became the first woman elected to sit on its Council. In 1913 she was made President of Section K (Botany) of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, the first woman to be made Section President in any field. Despite ill health in her final years, she was elected President of the Federation of University Women, and as World War I began Ethel worked tirelessly to set up a national register of women qualified to do work of national importance.

Her obituary ends by saying that:

‘her genial personality was appreciated by all who knew her, and her great heart and lofty mind inspired the closest affection’.

Yes, but who was Ethel Sargant, really?

All those neatly worded biographies and obituaries give us a particular image of Ethel as a privileged pioneer who made a name for herself in botanical research, and actively supported botanists, women, and women botanists in her network while being supported by others in return. But apart from the word “genial” we don’t have any real sense of her personality.

So we hit the archives again, this time at Girton College. We wanted to discover what Ethel was like in her student days – decades before she became the respected botanist ‘Miss Sargant, FLS’.

We searched through the Girton Review, a summary of the College’s clubs and societies published twice a year, for nuggets of character gold. We quickly found some: Ethel was a member of the Girton College Debating Society, and in 1883 it was her chance to pick the topic:

The debate was held on Wednesday, May 2nd.

E. Sargant proposed that

‘Early Rising is a pernicious and degrading practice.’

K. Birrell opposed. Ayes, 14; Noes, 24.

Suddenly, Ethel is brought to life! Glittering with good humour, this member of the anti-mornings brigade was prepared to defend her beliefs in a public forum—despite being voted down 2–1. This little corner of Girton history gave us something authentic to play with on stage. We’ve even included that debate title in the show’s dialogue, as Ethel’s excuse for missing her first early morning lecture in Advanced Calculus. You can see it here at 2 minutes 40 seconds into this video:

Girton Archives also revealed that Ethel was elected as a Captain of the Fire Brigade, but only briefly (perhaps the early morning fire drills proved too ‘pernicious’…?) and alongside hosting late night lemon squash parties she founded the ‘Bookworm Society’ with fellow student Charlotte Angas Scott. Another of our five main characters, Charlotte was a mathematician who passed the notorious Tripos exams in 1880 in eighth place – the highest of any woman at that time. Despite this achievement, she was denied full recognition by the University because of her gender. A Girton Songbook in the archives revealed that Ethel wrote new words to a traditional melody to tell Charlotte’s story, so that Girtonians could celebrate her in song. Will Ethel’s lyrical tribute appear in the show? Of course it will! Here’s a version of it sung by Girton College Choir.

On the same trip to Girton College Archive, we discovered that one day in 1886, the committee of Girton College “Browning Society” poetry club decided to close it down, due to lack of members. They voted to spend the remaining funds of 1 shilling 7 ½ pence immediately… on chocolates. This was such a great reminder that no matter how pioneering these women were, and no matter what extraordinary lives they went on to lead, at Girton they were still just a group of young women enjoying their first real taste of freedom and autonomy. And nearly two shillings of chocolate.

Ethel the Activist

My next archive visit, to The Women’s Library collection at LSE, revealed two completely different and unexpected sides to Ethel’s character that we had no idea about.

Slotted into a letter from Ethel to the secretary of the Federation of University Women, Ida Smedley Maclean, was a cutting from the Cambridge Daily News dated 25 March 1914 with the following headline:

WOMEN AND TAXES

A Lady Scientist’s Protest

‘THE ONLY RESOURCE’

Sale of Goods at Girton

It described how a 50-year-old Ethel had refused to pay the King’s taxes, and her debt had now reached a total of £9 and 18 shillings – around a month’s wages for a skilled tradesperson.

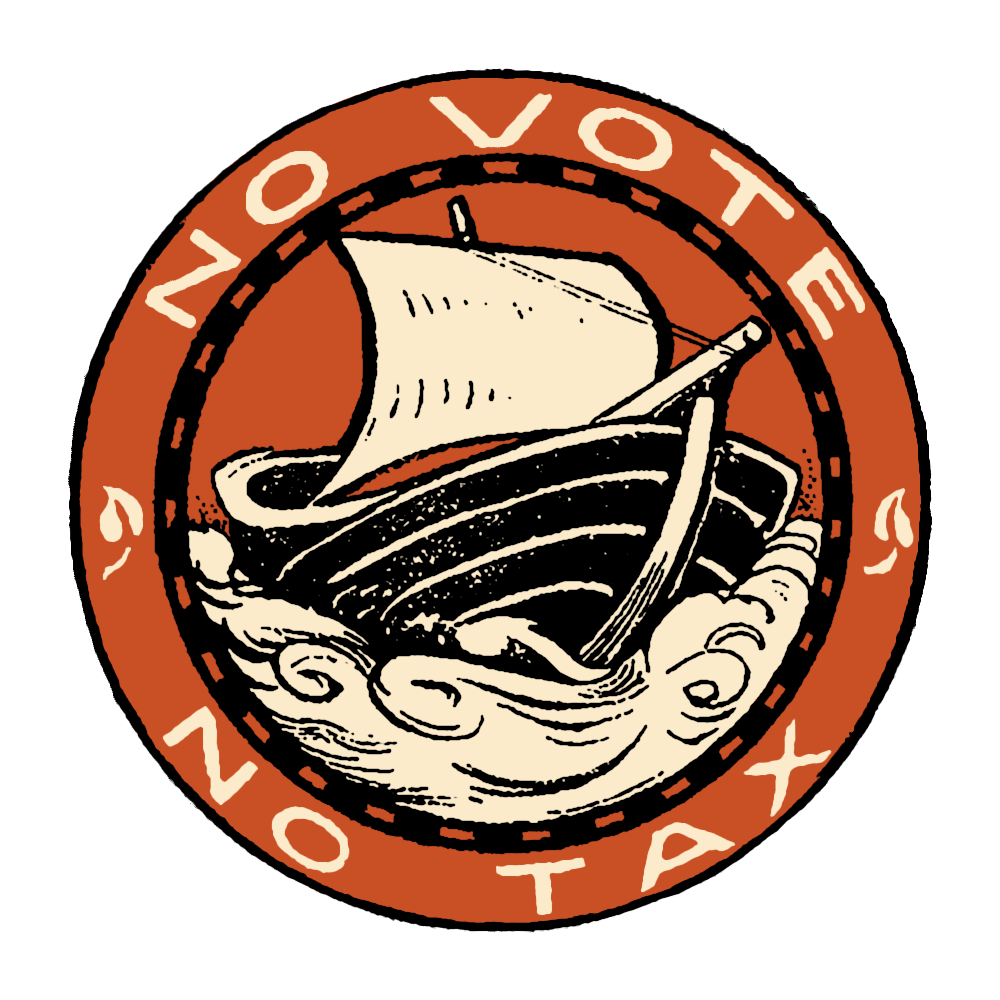

The article describes Ethel’s very clear reason for not paying her dues, which echoed the call to arms of both the American Revolution and parts of the British Suffrage movement: ‘NO TAXATION WITHOUT REPRESENTATION!’. It turns out that Ethel was an active member of the Women’s Tax Resistance League along with her sister Mary Sargant Florence, a professional artist who designed the organisation’s logo:

While living what appeared to be a genteel, ladylike retirement in Girton Village near Cambridge, Ethel was actively breaking the law in order to make a very public protest. In response, the local Collector of Taxes ran an auction to sell some of Miss Sargant’s possessions to settle her debt. Little did he realise that Ethel would turn the auction into a kind of Protest Party, attended by local villagers, Cambridge students and professors, visiting Londoners, and other members of the Women’s Tax Resistance League.

With an atmosphere more like a festival than a distrainment auction, Ethel gave a grand speech after the sale to explain that a woman’s right to vote was the only cause that could make her break her law-abiding tradition of a lifetime. She also expressed frustration at the slow progress being made by peaceful suffrage protests, and the lack of reporting in the press, reported without irony by the Cambridge Daily News reporter:

Letters on the subject were rarely published. But when a militant suffragette broke a window in Regent Street the papers were full of it. ‘What is left for us who break no man’s windows to do?’ asked Miss Sargent (sic).

Digging deeper into more of Ethel’s life by searching academic articles about her, I found that this wasn’t Ethel’s first involvement in politics and activism. Years earlier, she spent her own money to support the Tunbridge Wells branch of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, recruiting her professional artist sister Mary to create posters for the window displays. A supporter of the Liberal Party – who she thought most likely to grant women the vote if elected – Ethel also paid for the hire of a motor car decked out in the party’s colours to drive around the area and mobilise voters during the 1910 General Election.

Ethel spent much of her life supporting those around her, especially the lab assistants and students that she mentored at “Jodrell Junior”. One of her favourites was Agnes Arber, who became a respected botanist in her own right, and hundreds of pages of Ethel’s letters to her protégée are preserved in Girton College’s archive. Although they agreed on many things, the suffrage movement was not one of them: Agnes did not support the Votes for Women campaign. But, in a great example of ‘agreeing to disagree’ that feels quite rare nowadays, Ethel wrote to Agnes about her suffrage activities but never forced her views, or allowed their different opinions to threaten their friendship. Writing to Agnes in 1910, she added a section about her campaigning activities that started with this note:

“All this last paragraph in a whisper—you needn’t hear it unless you choose!”

So our lens on Ethel widens… from quietly privileged pioneer to loud law-breaker who threw away the rulebook when she saw a way to fight injustice – but never let a difference in values, however strongly held, destroy a good friendship.

Ethel the Agent of Chaos

As I looked further into Ethel’s letters to Ida at the Women’s Library, they didn’t just reveal this principled suffragist side of Ethel. They also show parts of her personality that we had no clue about from all our research so far… and this Ethel is pure chaos.

The article above was sent with a letter from Ethel, apologising to Ida for having neglected her duties as President of the Federation, but hoping that the newspaper cutting would explain why she had been particularly busy of late. In just a small handful of letters I discovered a whole mountain of Ethel chaos:

- Not realising she had been elected President for two years, thinking it was only a one-year term, and expressing her annoyance that they had not elected someone from Oxford instead.

- Realising that she’d written upside down on letterheaded paper, and apologising in a “PS”.

- Missing her train to London for a Federation meeting because she looked at the wrong day’s timetable.

- Then proceeding to leave the “god-forsaken” station and get lost on the way back to her own house!

This brought a whole new Ethel to life for us, and has helped us create our three dimensional version of her character that we’re bringing to the stage: Yes, our Ethel has a ‘great heart and a lofty mind’ but also has a wicked sense of humour, is constantly surrounded by a cloud of chaos, and shows a real talent for insubordination when required!

REFERENCES:

- Join the Linnean Society here, and read the extended version of this blog in the December 2025 issue of their online magazine.

- Read more about Ethel and her botanical work here:

- ‘A Theory of the Origin of Monocotyledons, founded on the Structure of their Seedlings’ by Ethel Sargant.

- Miss Sargant and a Botanical Web by Peter Ayres.

- The Door was Opened, published by The Linnean Society with a chapter about Ethel by Prof. Dianne Edwards (to whom we are grateful for her insights and encouragement!)

- Our huge thanks also go to Girton College Archive and The Women’s Library at LSE for assistance in searching their collections.

Leave a comment