One of the central driving forces behind our version of the show’s main character, Hertha, is her powerful sense of justice. She has to do the right thing, whatever the cost. First she feels compelled to form a Fire Brigade, then later in the show she starts a campaign for women at Cambridge to be awarded equal degrees for work that is equal to the men’s. Taking on these all-consuming projects causes Hertha to sacrifice her academic goals, her health, and her family’s hopes… but she still does them, because they’re the right thing to do.

The real Hertha Ayrton also strived for justice, from a younger age than most, and continued to do so throughout her life. Here are three moments of protest from Hertha’s life that have helped us to understand more about our Fire Brigade’s founder.

1. HUNGER STRIKES

Biographer Evelyn Sharp describes a time at school when young Hertha was accused of some misbehaviour that she wasn’t responsible for, but the teachers refused to believe her. To prove her innocence, she came up with the idea of a hunger strike:

“For two-and-a-half days she came to every meal but steadily refused to touch food, until, both alarmed and convinced against their will of her innocence, her harassed elders had to give in and concede her point.“

The concept of hunger strikes as a weapon in the fight for social justice came full circle for Hertha decades later. Members of the Suffrage movement used the same technique to protest against their imprisonment, including the leader of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) Emmeline Pankhurst. When prisoners like Mrs Pankhurst were considered too weak from starvation to stay in prison, they were released “on license” to be nursed back to health by their friends – and then swiftly re-arrested in a legal process nicknamed the “Cat and Mouse” Act.

As well as donating significant sums to the WSPU, Hertha was one of a network of women who turned her houses into nursing homes for Mrs Pankhurst and others, and suffered the consequences for doing so. Norfolk Square in London, the location of both her home and her home-laboratory, became over-run with Press photographers, reporters, and her house fell under 24 hour observation by the police – a reasonable policy on their part, as the “mice” had a tendency to disappear in an attempt to avoid re-arrest… Hertha even went as far as using her own bank account to secretly send WSPU funds abroad for safekeeping, when rumours spread that the government was about to confiscate the organisation’s assets.

2. BLACK FRIDAY AND WOMEN’S RIGHT TO VOTE

Although Hertha was never arrested herself, she planned her scientific work around a spell in prison – just in case. Her biographer writes:

“Mrs. Ayrton’s participation in the militant demonstrations of November, 1910, led to the postponement of her paper, “On some new Facts connected with the Motion of Oscillating Water” as she fully expected to be in prison on November 21, the date on which she had engaged to read it before the Royal Society.“

These “militant demonstrations” included a march on Parliament scheduled by the WSPU for Friday 18th November 1910, now known as Black Friday. As a well-known public figure and prominent Suffrage campaigner, Hertha walked in the front group of around 300 marchers. Many of the protesters following her were assaulted and badly injured in clashes with the police and bystanders, and around half were arrested for “disorderly” conduct.

Almost all of the protesters were blocked from entering Parliament, but three were allowed inside to put their case to Prime Minister Herbert Asquith: Mrs Emmeline Pankhurst, Mrs Elizabeth Garrett Anderson and Mrs Hertha Ayrton. Asquith refused to meet them, however, and they were soon escorted back outside. Four days later, Hertha joined another WSPU protest, this time headed for Downing Street and the Prime Minister’s home. Her experience on this march, which became known as the Battle of Downing Street, was quite different. After seeing garbled Press reports that misrepresented the roles of the WSPU and police, Hertha sent (unpublished) letters to the Times newspaper in an attempt to correct their reporting:

“I was marching immediately behind Mrs. Pankhurst when she entered Downing Street, but was prevented from reaching No. 10 by an attempt at strangulation on the part of a policeman … Twice, policemen seized me by the throat.”

But still no arrest. Hertha’s daughter, Barbara “Barbie” Ayrton-Gould, who later became a Member of Parliament herself, had more “luck” at being arrested at a protest a few years later, as Hertha reported in a letter to her stepdaughter, the writer and activist Edith Ayrton Zangwill:

“Barbie is in Holloway, having, with all the others, refused bail… She is to be tried on Wednesday. I am very proud of her.”

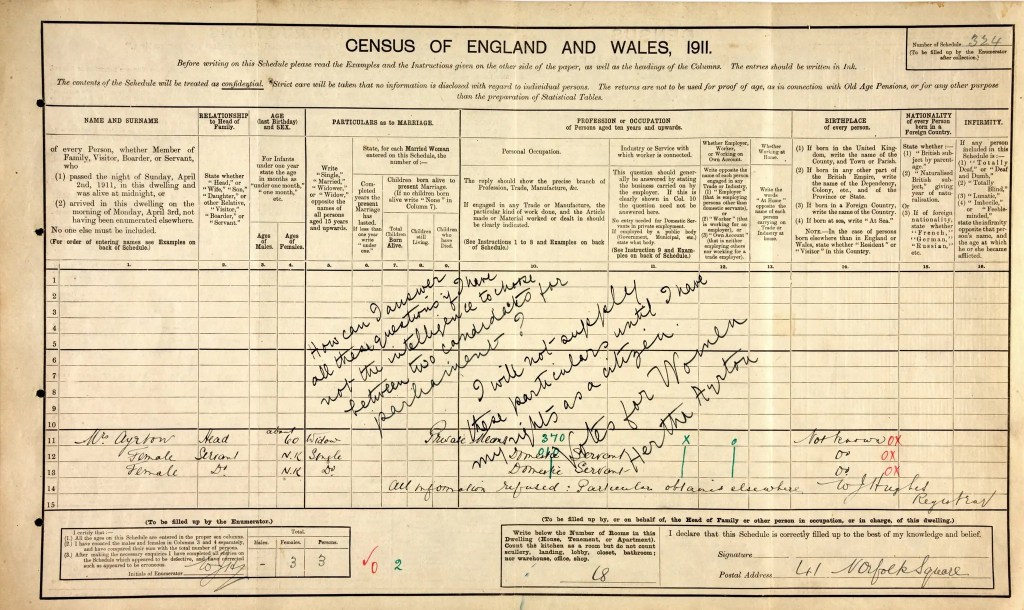

Hertha continued to protest for women’s right to vote in many different ways, including joining the ranks of 1911 Census Boycott, organised by suffrage societies including the Women’s Tax-Resistance League (“No Vote No Tax”) which another of our main characters Ethel Sargant was an active member. Instead of completing her census form correctly, Hertha risked a £5 fine by covering it in her elegant handwriting as follows:

“How can I answer all these questions if I have not the intelligence to choose between two candidates for parliament? I will not supply these particulars until I have my rights as a citizen. Votes for Women.“

3. MARIE CURIE AND MISINFORMATION

Hertha met fellow scientist, and discoverer of the element Radium, Marie Skłodowska-Curie, at the Royal Institution in June 1903. Marie sent Hertha an autographed copy of her PhD thesis on Radioactivity, and they became firm friends for 20 years until Hertha’s death. Evelyn Sharp’s biography of Hertha is dedicated “To Madame Curie: this memoir of her friend”. After the death of Marie’s husband Pierre, articles appeared in the British Press that misattributed Marie’s discoveries as her late husband’s work. This must have stung Hertha who – like Marie – also worked in the same scientific field as her husband, but very rarely together in an effort to avoid exactly this situation. Hertha took to defending the Nobel prize winner’s work, writing in a letter to the Westminster Gazette in March 1909:

“Errors are notoriously hard to kill, but an error that ascribes to a man what was actually the work of a woman has more lives than a cat.“

Throughout her life, Hertha found that her outspoken support of causes she believed in – and her outspoken style in general – meant that some parts of established society were quick to reject her achievements and belittle her scientific career. When Chemist Henry Armstrong was (perhaps ill advisedly) asked to write Hertha’s obituary, he came to a conclusion that focussed more on her husband, William Ayrton, than the subject he was supposed to be writing about:

“She was a good woman, despite of her being tinged with the scientific afflatus… (Mr Ayrton) should have had a humdrum wife who would have put him into carpet-slippers when he came home, fed him well and led him not to worry either himself or other people, especially other people; then he would have lived a longer and a happier life and done far more effective work, I believe.“

Hertha’s life choices often came at great personal cost. But she still continued to do “the right thing” and fight injustice where she saw it.

We’ve written a song for Hertha that comes almost at the end of the first half of the show, where she finally loses her temper at the demeaning, sexist behaviour of her male Cambridge lecturers. As her righteous anger takes over her, she tears into the men in the room – and says a few things that even she might come to regret…

REFERENCES

- Hertha Ayrton, A Memoir by Evelyn Sharp

- Women’s History Month: Hertha Ayrton by Clare Jones

- The Scientist Suffragettes by Katherine Emery

- Hertha Ayrton and the Admission of Women to the Royal Society of London by Joan Mason

- Almost a Fellow: Hertha Ayrton and an embarrassing episode in the history of the Royal Society by Dr Felicity Henderson

- Black Friday

- The Battle of Downing Street

- Barbara Ayrton-Gould

- A 1911 Census enumerator troubling himself about Mrs Ayrton

- “No Vote No Census”: Talk for National Archives by Elizabeth Crawford

- Hertha Marks Ayrton and the Fight for Fellowship: Video from Objectivity and Royal Society on YouTube

- Hertha Ayrton: Great Lives on BBC Radio 4

- Marie Curie – New Material Uncovered in IET Archives

Leave a comment